Research article / Open Access

DOI: 10.31488/bjcr.171

Foundations for Healthcare Workers in West and Central Africa

Wilson Astudillo1, Fernando Rivilla1, Jhon Comba1, Michael Silbermann*2

1. Palliatives without Borders, Spain

2. Middle East Cancer Consortium, Israel

*Corresponding author: Michael Silbermann, Middle East Cancer Consortium, Israel

Abstract

This article attempts to promote a better understanding of the health situation in West and Central African countries. In this environment, where there is a marked shortage of adequate health structures, there is a great need to alleviate the pain and suffering related to cancer and other chronic diseases. We stress the importance of acting with the utmost respect for the dignity of the sick and trying to do the best one can, based on known ethical principles, taking into account the health deficiencies and cultural diversities. We highlight the role of further education for healthcare workers to progress and improve the system. These healthcare workers need special support and protection, as the context in which they work has become increasingly complex.

Keywords: cooperation, African health care, suffering, high-quality care, palliative, planning

Introduction

The desire to collaborate with others affected by either a pandemic or natural disaster, or with those in need of assistance due to a weak healthcare system or poverty, is a way of initiating solidarity across borders and recognizing that severe suffering can affect anyone, regardless of the environment in which they live. It is essential to coordinate as a team with other professionals in the area in order to assess a patient and understand the context of his or her environment, while respecting the individual’s and family’s autonomy, dignity, and values.

Health Needs

The lifespan of the majority of Africans is, on average, 14 years less than the global average, particularly in Sierra Leone; this may be due to malnutrition, poor hygiene, environmental and water pollution, unemployment, an increased prevalence of HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and the lack of a good basic health infrastructure [1]. In 2005, the World Health Organization (WHO) proclaimed that all people should have access to health services, regardless of their economic status, and considered it essential to improve the way resources are managed or allocated to this sector [2].

Maternal and Infant Mortality

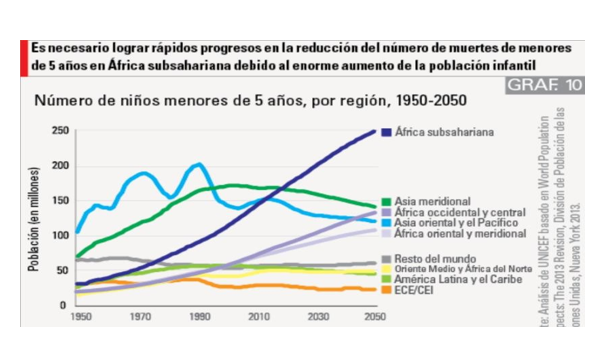

The African population has the lowest survival rates and worst prognoses in the world, with cancer being one of the leading causes of death. Countries such as Sierra Leone, Liberia, Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Gambia, Mauritania, and Guinea Bissau have the highest maternal mortality rates. In 2015, 303,000 women died from complications of pregnancy and childbirth [3,4]. Most of these deaths occurred in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), with Liberia, Nigeria and Sierra Leone, which belong to sub- Saharan Africa (SSA), having the highest rates: 725/100,000, 814/100,000 and 1,360/100,000, respectively [1-5]. Nevertheless, Africa has made much progress in this area, albeit in only four countries - Cape Verde, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, and Rwanda - and have reduced maternal mortality by more than 75%, as targeted by the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). This high maternal mortality is related to the low proportion of births attended by health professionals, the high rate of teenage pregnancies, difficulties in accessing family planning programmes, the shortage or absence of surgical services, abortions, sepsis or eclampsia not attended by health professionals, the lack of means to stop postpartum hemorrhage, or to non-pregnancy causes such as severe malaria [5-7]. The world's highest under-five mortality in Africa must be reduced as rapidly as possible and is due to: neonatal asphyxia (40%), prematurity and low birth weight (25%), infections (20%), congenital defects (10%) and acute surgical infections (3%) [5]. Malaria is the leading cause of under-five deaths, accounting for 10% of the total burden of disease in Africa (Figure 1). Rapid progress is needed to reduce the number of child deaths in sub-Saharan Africa due to the increase in the child population.

Figure 1:. Global Child Mortality. UNICEF, 2013 Review

Principles of Action

Four of the seven principles proclaimed as fundamental to humanitarianism by the 20th International Conference of the Red Cross [8] in 1965 form the basis of development workers’ actions:

• Humanity: To prevent and alleviate suffering wherever it is found, protecting life and health, ensuring respect for the human being; to promote mutual understanding, friendship, cooperation, and lasting peace among all peoples.

• Impartiality: Not to discriminate on the basis of nationality, race, religious beliefs, gender, or political opinions.

• Neutrality: To take no part in hostilities or controversies of a political, racial, religious, or ideological nature; to strive only to alleviate suffering, giving priority to the most urgent cases.

• Independence: To maintain autonomy in order to be able to act in all circumstances, in accordance with the principles of humanity, impartiality and neutrality.

These principles of humanitarianism avoid the exclusion of care for patients with incurable illness and imply the recognition that suffering is universal and requires a response which cannot be indifference. They stand for respect for human dignity, for helping and protecting others, whoever they may be or whatever they have done,[9] for protecting life and health and serve not only to respond to disaster and disease, but also to prevent it. The Covid-19 humanitarian crisis, for example, has also affected children, adolescents and women; by 2020, according to UNICEF, 60 million children will be forcibly displaced within their own countries. Nine of the 10 countries with the highest neonatal mortality are involved in conflict [6].

Understanding the Situation of the Sick

In recent years, Africa has seen a rise in the rate of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, asthma, and circulatory diseases which, due to progressive urbanization, is overtaking infectious diseases as a cause of death. Coronary heart diseases, which have been rare in the sub-Saharan area (SSA) until recently, are increasingly present, especially with regard to hypertension. Multimorbidity affects one in four people and is associated with a higher symptom burden [10]. The reasons for this growth in NCDs are complex and multifactorial, and include dietary changes, radical reduction of exercise and, with regard to asthma, increased exposure to allergens [10].

For healthcare workers traveling to African countries, it is essential to first contact health institutions or NGOs in that country in order to attain their support, which will help to better understand the patients’ lives, their environment, their home, and community, and to ensure the continuity of managing their health. As professionals, we try to develop good communication, as empathetic as possible with the patient and their family, to find out how they feel and how their illness has affected them, as well as the evolution of the illness, the care and previous treatments they have received, if they have tried traditional medicine, and to find out more about who this person is: the patient´s origin; and to evaluate, detect, manage and alleviate their suffering which is, essentially, the goal of all these actions [11,12].

Working as a team with local staff improves communication and the understanding of what the patient is experiencing, especially on this continent where there are more than 2,510 languages, representing one third of all languages on Earth (e.g. South Africa has 11 official languages), highlighting the fact that most indigenous African languages do not have a word for cancer [12]. Non-verbal communication is of great importance when detecting suffering and establishing a relationship with others, as “with a single look, with a single gesture, we have the power to reaffirm the sufferer in his/her identity, or the opposite, to confirm that he/she is not just an unpleasant object, a kind of burden that everyone wants to discard” [11]. Therefore, important steps are to:

• Detect the most bothersome symptoms

• Explore how symptoms are experienced and how they influence discomfort

• Orient your diagnosis

• Seek to treat or eradicate the symptom, if possible, or give a hospital referral

• Monitor progress in order to maintain or change treatment

• Assess anxiety or depression and use appropriate techniques to alleviate them

• Try to help the patient find meaning in his or her life

Table 1:Pathologies with Disease-related Suffering

| Atherosclerosis | Prematurity |

| Chronic ischemic diseases | Viral hemorrhagic fevers (Ébola) |

| Non-ischemic heart diseases | Poisoning |

| Congenital malformations | Leukemias |

| Degenerative CNS respiratory diseases | Respiratory diseases |

| HIV/AIDS | Malignant neoplasms |

| Inflammatory CNS diseases | Musculoskeletal disorders |

| Obstetric trauma | Renal Failure |

| Protein malnutrition | Tuberculosis |

| Viral Processes - pandemics Covid-19 |

Physical symptoms, particularly pain, must be managed in order to access the mental, social, and spiritual elements that may affect the sufferer. Although it is not always possible to eliminate symptoms, it is possible to attenuate their physical, mental, Emotional, and spiritual effects. If treatment considered adequate has been given and there is no response, the patient should be reassessed for other possible organic causes, but if, despite this and modification, there is no change, other psychosocial causes such as fear and anxiety should be explored. In cases of humanitarian emergencies and crises, large-scale events that can cause significant challenges to health systems and society, forced displacement, death, and suffering on a massive scale, it is not only essential for care to be directed towards saving lives but also for ethical and medical reasons, prevention, relief of pain and other physical and psychosocial symptoms [8,9].

Care Needs

The high mortality rates in LMICs from treatable causes, such as trauma and surgical wounds, maternal and newborn complications, cardiovascular disease and vaccine-preventable diseases, illustrate the magnitude and depth of a change in the quality of care, however, it is not enough that there is only access to care. High-quality, more specialized, longitudinal and comprehensive care could prevent 2.5 million deaths from cardiovascular disease, one million neonatal deaths, 900,000 deaths from tuberculosis and half of all maternal deaths each year [10,13]. High-quality care requires: an adequate assessment of asymptomatic and co-existing conditions; recommending examinations and tests to enable diagnosis; timely and appropriate treatment or referral if hospital care or surgery is needed; and the ability to monitor progress and adjust treatment as necessary [12].

Prevention and early detection of illness is an important function of quality health systems. For example, prenatal care must include examining blood pressure, blood and urine tests for pre-eclampsia, diabetes, nutritional deficiencies, infections and other risks of pregnancy, as well as postpartum check-ups for bleeding, perineal rupture, signs of infection, and hypertension [13]. The lack of available or inadequate laboratory and diagnostic equipment is, together with language, a barrier to proper patient assessment and diagnosis [14]. Simple materials such as glucometers and urine strips are only available in 18-61% of services in Mali, Mozambique and Zambia [15]. A study of 10 countries found that only 2% of health facilities had all eight diagnostic tests defined as essential by the WHO [16]. Anatomical pathology coverage in the African Academy of Sciences (AAS) is one tenth of that in rich countries [14]. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, only 4% of laboratories have been found to correctly identify the parasites that cause malaria and trypanosomiasis [17]. According to a study in six countries conducted by the WHO, only 20% of all women receive a mammogram, and only 1% in India and 2% in Ghana [18]. Another problem observed in 54 LMICs is that 35% of health facilities did not have hand-washing and soap facilities [19].

Delays in diagnosis can be very important to the survival of patients with breast and cervical cancers. Waiting longer than five weeks for a diagnosis can worsen survival for cervical cancer as well as for breast cancer, [10] and the wait can be even longer than 12 weeks. Misdiagnosis, in turn, has detrimental health consequences and contributes to treatment delays, antimicrobial resistance, and death. Diagnostic accuracy can range from 8-20% for non-severe pneumonia in children in Malawi [20]. Many patients remain untreated or undertreated for HIV, tuberculosis, hypertension, diabetes, and depression [9]. All tuberculosis patients should be tested for HIV due of risk factors common to the two infections. In the WHO African region, where the burden of HIV-associated tuberculosis is highest, 82% of patients with tuberculosis were tested for HIV [10]. Obstetric fistulas that develop in women with prolonged labor have severe social and health consequences and indicate very poor obstetric care and a health system failure [21]. Quality of care and lack of trust in primary care are the most common reasons for patients going directly to hospital. Improvement of the health system is justified on ethical, epidemiological and economic grounds because poor quality of care can lead to a very large macroeconomic burden, increased premature mortality, and inefficiency. Improvements in quality must start in the areas with the greatest quality deficits, with a primary focus on the care received by disadvantaged populations [10]

Suffering and Pain

Suffering and pain are expressed in a variety of physical and psychological forms and can be detected if there is a sensitivity to look for their causes, although the existence of multiple languages increases the difficulty of understanding their clinical picture. According to Chapman and Gravin,[22] distress is defined as "an affective, cognitive and negative state characterised by a threat to one's integrity, by the powerlessness to cope with this threat and by the exhaustion of personal and psychosocial resources to cope with it.” For the Hastings Center, "the threat posed to someone by the possibility of pain, Illness, or injury can be so profound as to equal the actual effects it would have on the body". Its origin can be multiple and summative, as shown in Table 2, below.

Table 2:Causes of Suffering

| Persistence of symptoms | Be ignorant of diagnosis | Depression - Anxiety |

| Poor symptom management | Loss of social role | Inappropriate situations |

| Undesirable reactions | Symptom recurrence | Feeling of guilt |

| Unfavourable prognosis | Feeling lonely, unloved | Conflicts - disagreements |

| Physical disturbances | Conspiracy of silence | Insufficient health support |

| Perceived hopelessness for the future | Inability to resolve conflicts | Fear of dying alone |

| Threat of imminent destruction | Negative thoughts | Anticipated grief |

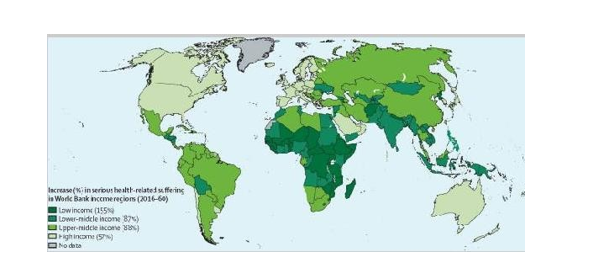

Patients with serious illness experience the angst associated with costs and, therefore, preventing this additional burden must be an essential component of quality health systems. The Lancet Commission report of 2018 [23] on Palliative Care (PC) and Pain Relief found that 25 million people died in 2015 with severe illness-related suffering (SHS), which is suffering that alters their mental, social, and spiritual functioning and cannot be alleviated without medical intervention. Of these, 2.5 million were children, mostly from poor countries. Based on this report, KE Sleeman et al.[24] have estimated that, by 2060, 53 million people (48% of all global deaths) will experience this type of suffering, and that 83% of these deaths will occur in LMICs. The burden of this suffering in 2060 will almost double that of 2016, with the greatest increase in people over 70 (183% increase), suffering from cancer (109% increase) and dementia (264% increase), and will affect the least developed countries, meaning that a greater proportion of people will suffer before they die.

Sleeman's study has its limitations as it is based on mortality cause records, available for only one third of the world's population. Currently, there are uncertainties about causes of death, with a deviation rate of 1% in developed countries to 20% in sub-Saharan Africa. Improving these registries will allow better projections of health system design and PC needs, which are increasingly recognised by international health organisations as the cornerstone of global health and should be considered for integration into health systems, as they not only increase quality of life, symptom control and patient and caregiver satisfaction, but do so at a lower cost than the alternatives (Figure 2).

Figure 2:Increase in severe suffering (SHS) from 2016 to 2031, by region [24]

Pain

Pain, which is a basic component of suffering present in a multitude of diseases and clinical situations, both acute and chronic, is one of the most disabling elements for patients who suffer from it and can even limit the therapeutic approach to other pathologies. Every year in low- and middle-income countries (83% of the world's population) patients with advanced cancer do not receive adequate pain treatment and urgent action is needed to remove bureaucratic and ideological barriers to the appropriate use of analgesics [10].In humanitarian emergencies and other crises, pain is the most severe cause of suffering; there are multiple medical reasons for intensive pain control for any patient, particularly for those who have traumatic and post-operative pain. Many victims of humanitarian emergencies suffer from multiple symptoms of varying chronicity and may experience different types of pain in several areas at the same time, each requiring specific treatment, depending on its etiology, location, chronology, and intensity. It is very useful to remember their indirect signs, particularly if the patient is not fully conscious [8-10].

Table 3:Indirect Signs of Pain

| Psychomotor atonia |

| Appearance of the face when experiencing acute pain |

| Uncoordinated movements |

| Moaning, screaming |

| Sensitive, painful areas |

| Repetitive skin rubbing |

| Sudden confusion |

| Profuse sweating |

| Refusal to mobilize |

Pain can be: a) somatic, such as bone or muscle pain which is well localized, continuous and described as dull, biting or cutting, and can ,be relieved by NSAIDs and paracetamol; b) visceral, which originates from organ distension or growth, tumor infiltration and algetic or inflammatory substances in the vicinity of neoplasms. It is poorly defined, poorly localized and severe and its relief, in addition to the above drugs, may require corticosteroids or antispasmodics; c) neuropathic, caused by a lesion of the somatosensory nervous system, both central and peripheral, which is described as a constant, irritating, burning sensation alternating with paroxysms of an electrical Nature; it can be relieved by antidepressants and anticonvulsants, and d) mixed, as in oncology, where viscera, muscles or bones may be affected progressively or simultaneously, with each condition having a different mechanism of pain production. Effective pain management requires providing information to patients and their families on pain relief, how to administer medication, how to avoid pain peaks, how to decide on dosage, route, and frequency over a 24-hour period, technical aspects of continuous infusion pumps and keeping records of pain level in relation to the medication, its response, and frequency.

Patients most at risk for inadequate pain management are the elderly, over 85 years of age, marginalized racial minorities, women, patients with poor financial means, sensory deficits, and polymedicated patients. The Lancet Commission report of 2018 notes that 1/3 of children 15 years and older who died in 2015 (almost 2 million) experienced severe illness-related suffering, 98% of whom lived in poor countries. Inadequate postoperative pain control produces a "wide spectrum of physiological and immunological effects and tends to be associated with poor surgical outcomes". Other undesirable effects include cardiovascular disease, hypertension, arrhythmias, heart attacks, hemorrhage, stroke, venous and pulmonary thrombosis, pneumonia and atelectasis, increased tissue expenditure and hypercaloric, impaired immune function and increased risk of infection, hyperalgesia, development of chronic pain or central sensitization, as well as anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance, and demoralization.

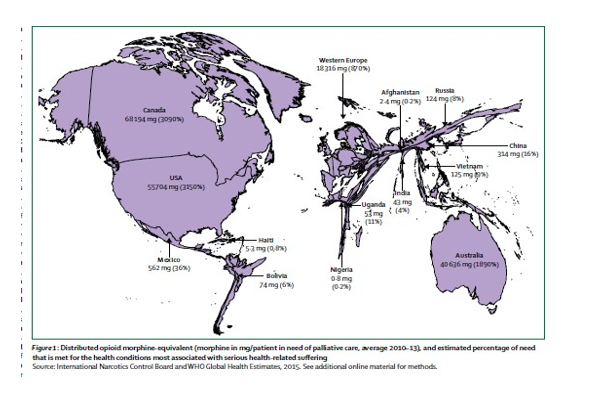

While the WHO recommends opioids for the relief of moderate to severe cancer pain, and morphine as an essential drug for pain relief as it is less expensive and more effective, there is a wide gap between developed countries and poorer nations, which use only 6% of the total. According to data from 2010- 2013, of the 298.5 tons of opioid-equivalent drugs used globally, only 100 kg (0.1 tons) were distributed to resource-poor countries, which would cover less than 2% of their palliative needs. Uganda, for example, used 11% and Nigeria 0.2%. In 2013, the average morphine consumption in Africa was 1.85 mg/person, much lower than the 45.11 mg/person in Scandinavia, seen in Figure 3 [23]. Barriers to its use include overly restrictive laws, opiophobia, lack of training of professionals in its use, and an underestimation of the need for opioids that are produced or need to be imported (Figure 3).

Figure 3:. Global distribution of morphine-equivalent opioids between 2010-2013 [23]

HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria

The global HIV epidemic has changed dramatically since the advent of antiretroviral therapy, but the catastrophic transmission rate of the HIV virus, faster in Africa than elsewhere in the world, has produced not only individual tragedies but also a host of social and economic problems. HIV/AIDS presents in many forms and dominates practice in many hospitals and, together with tuberculosis and malaria, may be the cause of low life expectancy, especially in Sierra Leone and Côte d'Ivoire [11,25]. Two-thirds of those affected worldwide live in Africa, accounting for 75% of all deaths. In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), where 90% of the 2.3 million children with HIV reside, the highest rates of Kaposi's sarcoma, one of the most common cancers on the continent, are strongly associated with HIV/AIDS infection. Antiretroviral combination therapy (HAART) in carriers can produce marked reductions in disease and deaths and is the best palliative therapy [11,25]. With HAART, infections have decreased by 35% since 2000 and mortality by 42% since 2004. Without HAART and co-trimoxazole prophylaxis, about one-third of HIV-infected infants die annually and 50% die within two years [10,25]. According to The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), in LMICs in 2017 only 71% of people on HAART achieved viral suppression and only 10 countries had 90% viral suppression [23,26]. In Kenya in 2015, the delivery of a comprehensive package of HIV services to sex workers reduced sexual transmission from 27% to 3%. Cameroon has a high rate of HIV/AIDS carriers. Malaria and tuberculosis also continue to carry a huge burden. In countries with treatment-resistant TB, success rates range from 50-85% [10]. Seventy-eight million children under the age of five have malaria and the incidence of TB is 363 cases/100,000. These figures show the need for better monitoring, treatment, and counselling of patients with manageable conditions in LMICs.

Palliative Care

The WHO considers that Palliative Care (PC) and Pain Management (PM) should always be offered, from the time of diagnosis, to prevent and alleviate suffering and improve the well-being and dignity of patients, especially in the final phase of degenerative diseases, AIDS, cancer, and multiple organ deficiencies. PCs promote early identification, appropriate assessment and treatment of problems encountered in all circumstances. As mentioned, they are applicable from diagnosis and throughout the course of the disease, in conjunction with other therapies intended to prolong life, and provide support for the patient and family throughout the course of the disease and during the bereavement process that follows. PC and PM are not an alternative to disease-modifying treatments, rather a complement at all levels of the health care system - improving quality of life, continuity of care, strengthening care and even survival. PC and PM stimulate active participation of communities and their incorporation into health systems will lead to universal coverage [8,9,11,23].

The Lancet Commission report of 2018 called for all countries in a humanitarian crisis to ensure universal access to a package of essential medicines and palliative care in order to maintain or improve the well- being of those who cannot be cured, whether acutely or chronically ill. About 50% of those who die with HIV and 80% of those who die with cancer need pain treatment for an average of three months. This is 3% of the usual cost of other packages, ranging in price from $0.7 to $ 2.5/person/year, making it more easily accessible, and can provide significant relief of Subject Global Evaluation (SGE); it contains generic drugs for relief of the main symptoms and pain, including morphine, both injectable and immediate-acting oral (Table 4). This package needs to be available in all hospitals and health centres and physicians should know how to prescribe and use it properly, as it is not only essential for the control of moderate to severe cancer pain, but also for terminal dyspnea that cannot be relieved by any other means. It is estimated that only 14% of people in need of care receive it, and most of these live in rich countries.

Table 4:Essential Package of Palliative Care and Pain Relief Health Services [23]

| Essential Medicines | amitriptyline, bisacodyl, dexamethasone, diazepam, diphenhydramine (clorpheniramina, cyclizine or dimenhydrinate), fluconazole, fluoxetine or other ISRSs (sertraline and citalopram), furosemide, hyoscine butylbromide, haloperidol, ibuprofen (naproxen, diclofenac or meloxicam), lactulose (sorbitol or polyethylen glycol), loperamide, metoclopramide, metronidazole, morphine (oral immediate-release and injectable), oral and injectable), naloxone parenteral, omeprazole, ondansetron, paracetamol and paraffin gel. |

| Medical Equipment | Pressure sore-reducing mattress, nasogastric drainage or feeding tube, urinary catheters, opioid lock-box, flashlight with rechargeable battery (if no access to electricity), adult diapers (or, in extreme poverty, cotton and plastic) |

| Human Resourses | Doctors (specialists and general, depending on level of care), Nurses (specialists and general), Social workers and counsellors, Psychiatrists, psychologists, or counsellors (depending on level of care), Physical therapists, Pharmacists, Community health workers, Clinical support staff (diagnostic imaging, laboratory technicians, nutritionists), non-clinical support staff (administration, cleaning) |

Opioids are needed to treat traumatic injuries and post-operative pain. In Haiti, after the 2010 earthquake, there was a huge need for painkillers but only anti-inflammatory drugs were available, so they had to be imported urgently. Some patients were even taken to the US to alleviate their symptoms. The lack of painkillers for injuries, trauma, post-surgery, and rehabilitation increased disability. Similarly, during the Ebola epidemic, there was a great need for symptom and pain relief but a marked shortage of morphine. For these reasons, all humanitarian organizations should introduce palliative education to their aid workers and continue to search for methods to prevent and alleviate suffering caused by these tragedies. The principles of humanitarian action and impartiality require that all patients receive PC and are not abandoned for any reason, particularly when they are dying [8-11].

More than half of resource-poor countries have no palliative care activities or hospices for either children or adults. The lack of PC provision will be catastrophic for countries with vulnerable health systems where palliative needs will be increasing. For these reasons, it is an ethical and economic imperative for governments to plan and provide services, education and medicines to reduce suffering; further research is needed regarding how such services could be developed and implemented in various populations in crisis.

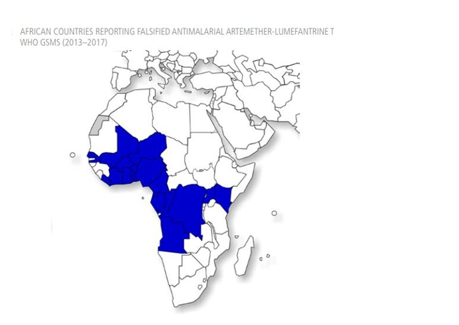

Medicines Review

A very important element for healing is to know what medicines to administer; special attention should be paid to the fact that medicines are often purchased in markets outside the usual circuits, of which 40-60% are known to be fraudulent (Figure 3). The WHO estimates that about 100,000 people in Africa die each year from counterfeit medicines that do not meet the normal quality, safety, and efficacy assessments and can aggravate the disease or produce many side effects, resistance, etc. The American Society for Tropical Medicine reported in 2015 that about 122,000 children under five years of age died in SSA from poor quality antimalarials. Thus, there is clear evidence that resistance to artemisinin, the most important antimalarial, appeared in Africa, where 38-90% of this drug was found to be substandard or counterfeit. The market for counterfeit or substandard medicines can generate 20 times more money than the sale of heroin. Poor legislation, weak health systems and widespread poverty are the factors favoring this parallel market. Since 2013, Africa has been importing 94% of its medicines and 42% of the world's seized adulterated drugs are found there. Africa produces less than 1% of its vaccines (Figure 4) [27,28].

Figure 4:African countries reporting falsified antimalarial, Artemether-Lumefantrine WHO's Global Surveillance and Monitoring System (GSMS) for substandard and falsified medical products (2013- 2017)

The Action of the Health Co-Operant

Although there are various ways in which one can help, great strides to alleviate serious health-related suffering can be made via cooperation with direct medical and surgical care, with actions that allow the real needs of those who suffer most to be met, wherever they may be, in an efficient and more focused way; this pertains not only to health, but also to reinforce the rights of the sick and their families. It is very useful to work as a team with the motto of ‘doing the best you can’, working within the location and with the best materials you can attain on the spot. Working as a team helps to share these challenges and to adapt to the context in which we live and work; it especially helps to feel as part of a team in times of uncertainty and sadness and to keep an open mind, to learn from others, and to eliminate prejudices.

It is essential that the ethical principles of nonmaleficence (do no harm), beneficence (acts of kindness and mercy to benefit others and to protect patients from harm), justice (patients with similar conditions or symptoms should receive equal medical treatment) and respect for autonomy, guide health and palliative care actions in response to the needs of the sick. Respect for patients' dignity and human rights will be shown by ensuring that they retain their decision-making capacity, giving them all relevant information about their condition and treatment in a language they can understand, and respecting their decision to accept or decline treatment. According to Diego Gracia, "there are several exceptions to the principle of informed consent, of which the physician should be well aware. One is incapacity (due to low-level or diminished sensory capacity); serious danger to public health; legal imperative (notifiable diseases); urgency (in the face of an urgent need, action is obligatory), even without informed consent; and therapeutic privilege, according to which the truth cannot be revealed when there are reasonable grounds for suspecting that it will cause the patient serious physical or mental harm" [29].

Patients shall not be discriminated against on the basis of race, religion, gender, age, or political affiliation and no person in need of care shall be ignored, forgotten, or abandoned [8,9]. Confidentiality and privacy should also be maintained, except in the case of a health need where only the minimum information necessary to protect public health should be disclosed. An action should be taken only if it is done solely with the intention of obtaining the best possible effect and relief of suffering in a proportionately serious case. As F. Rivilla says, "to care for others is to respond unconditionally to the suffering face; it is to embrace, encourage and humanize life to the end” [30]. Caring adds meaning to life both to the giver and to the receiver, and benefits the giver in terms of effort and knowledge. To love and care for others is to want them to exist, to hope that their lives continue to be important.

Cultural Factors

In order to be able to act well in health care in Africa, one must become familiar with the culture, languages, customs, values, and local diseases. Cultural traditions continue to shape people's beliefs about illness, the care they should seek, influence how they respond to illness, the medicines or foods that can help restore their health, and even their attitude toward death. In Africa, the ‘real’ world and the world beyond coexist and continually influence each other. The predominant belief that all matters of health and illness, including life and death, are predetermined may also contribute to the unwillingness of some individuals to be examined or treated for cancer. Turning to alternative healers and Traditional Medicines may delay diagnosis. Other contributing factors may be ignorance, youth, illiteracy, poverty, rural residence, superstition, denial, fear of mastectomy, and limited access to treatment centers, although a study in Nigeria revealed that over 50% of cancer sufferers waited an average of six months before reporting a breast lump, despite being enlightened [31].

Diseases in this area are not explained by etiological agents but by witchcraft and Traditional Medicine, the only avenue available in many sub-Saharan countries. This combines local remedies with anti-itch rituals and considers that the way to heal is to rid the body of evil spirits; the belief in witchcraft is widespread, which explains the delay in going to official medical centers. Many believe that an adversary or an evil spiritual force may be responsible for an illness [25].

One element to take into account in these countries is the role of the new churches of "revelation". For example, in Cameroon, pastors or priests offer to free people from illnesses by divine intervention with the laying on of hands, similar to what marabouts, sorcerers, and healers do. These churches, known as Wake, advertise on large billboards, posters, radios, and newspapers, all in exchange for money, and persuade the patient not to go to a hospital as there “they only act on the surface of the problem". The spiritual aspect even extends to healing, with the belief that even if the physical part has been healed, there is still another spiritual part that must also be healed, with their help.

Several studies have found that 70-80% of the global population turns first to traditional medicine [33,34] and that it is a valuable resource in one third of the world's countries; the Declaration of Alma Ata which, in 1978, expressed the need for urgent action by all governments, all health and development workers, and the world community to protect and promote the health of all people, states that "traditional medicine practitioners should be offered, as needed, with appropriate social and technical training, to work as a health team to meet the needs of the community",[33] i.e. incorporating indigenous health resources into primary care and assessing the current and potential role of traditional medicine, identifying potential areas of cooperation or conflict, and integration between modern and traditional medicine. In 2010, the WHO even launched guidelines for the registration of traditional medicines in Africa to ensure the safety and efficacy of products used in this practice [32,33].

In recent years, some countries have tried to educate healers in the processing and care of medicines in order to minimize the dangers from their use, and even to professionalize them by leading to some form of organisation and recognition which would be an important step towards increasing control of traditional medicine; however, the reality is that most healers are poorly educated and continue to operate freely and with little governmental supervision or control. Integration efforts have not yet been successful and traditional medicine has maintained its identity and vigor, with a parallel coexistence to traditional and modern health systems. Both the sick and the healers would like to collaborate with official medicine [23]. It is, therefore, in the interest of both traditional medicine practitioners and modern health practitioners to further promote a cooperation, to exchange information about diseases and to educate them regarding symptoms that accompany oncological diseases as well as other treatable concerns in order to increase patient referrals to hospitals [33,34].

Many people seem to welcome death with resignation, as they encounter it everyday and because they believe that it is only a transition from one stage of life to another. To understand this concept, it is necessary to know that natural death is not considered to exist here, except if one is very old. In the Beti culture of Cameroon, for example, death does not seem to exist, and this may be related to the African concept of life, where the dead have not died. Thus, the dead are buried next to their house, children sometimes play on the grave and families continue to keep their dead close to them, talking to them frequently as if they were still present. Even more haunting is the Africans' belief in reincarnation, claiming that there is a kind of back-and-forth trade between the world of the dead and the world of the living [25].

Recent Changes

Statistics show a downward trend in the number of people contracting HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis. The WHO’s intervention and the programs developed have played a key role. In the case of TB, the use of Directly Observed Treatment, Short-course (DOTS) is a strategy used to reduce the number of tuberculosis cases; healthcare workers observe patients as they take their medicine. DOTS has made a big difference - for malaria, the use of insecticides, bed nets, and the introduction of artemisinin, as well as for HIV/AIDS patients with access to antiretrovirals. Africa, however, accounts for half of all cases and deaths attributed to these three diseases, globally. Only a quarter of the African population now has access to an improved drinking water source and 16% of the population receives piped drinking water [35]. People with HIV are now living longer than before and may be able to establish families, work and lead normal lives. Often it is the salaried worker who is the carrier and dies, leaving the grandmothers to bury their children and try to care for their grandchildren. There are many orphans, and the new orphanages cannot meet the demand. In some places there has been a second generation of homeless infants.

On a positive note, Africa is close to achieving full primary school enrolment (only Niger, Chad and Côte d'Ivoire have youth literacy rates below 50%) and progress has been made in the field of technology. Mobile telephony has reached every corner of the continent, whereas only four countries had it in 1990. This has changed the lives of many people and communities, especially in sectors such as banking, political and social activism, education, entertainment, disaster management, agriculture, and health, and can facilitate the monitoring and follow-up of the sick and even curative and palliative treatment. The average number of people using the internet has also grown (Figure 5) [36].

The Role of Education in Change

Reducing the numbers of premature deaths from cancer and other non-communicable diseases is at the core of the WHO’s Global Program. Doctors and nurses in the SSA are not only working with tropical diseases, but also with common diseases, and it is necessary to consider the protection of women and children, to collaborate with universities at all levels, to prepare specialists to meet emerging health needs, to research new strategies to treat and eradicate neglected diseases, and to fight the stigma of misinformation and the underlying disease-poverty spiral. There is a need to improve equity and high-quality health care at all levels, in both primary and specialized care, and by establishing cancer centres. The lack of reliable data in Africa makes it difficult to assess the response, as 61% of its countries will not have adequate records to monitor progress in poverty reduction according to the Sustainable Development Goals (SGDs) by 2030. It is imperative to persevere in education, in the training of their children and young people outside all political and religious ideologies, to take up the path of self-esteem, to foster personalities, to believe that one can grow and develop according to personal work, and to seek the opportunity to show personal recognition for outstanding achievements [10]. Screening and vaccination programs are growing, and two major health developments in recent years have been the development of vaccines for Hepatitis B and the Papilloma virus. If 70% of all girls were vaccinated against HPV, there would be 178,000 fewer deaths annually, worldwide [35]. Vaccination is not recommended for everyone older than 26 years of age. HPV infections, genital warts and cervical precancers (abnormal cells on the cervix that can lead to cancer) have dropped since the vaccine has been in use. However, some adults ages 27 through 45 who are not already vaccinated may decide to get an HPV vaccine for new HPV infections. African countries need to open up their economies, embrace globalization, secure the legal framework for investments to flow in, and establish a genuine rule of law where laws, not men, rule.

Figure 5:. Types of interventions and where actions can improve the quality of Primary Care, according to the literature 2008-2017 [10]

Self-Care

Healthcare workers need support and protection, as the environment in which they work has become increasingly complex. They are sometimes in the midst of conflict, social and economic fragility, a global pandemic and climate crisis, all at the same time. They face considerable risks due to hardships and disasters where they wish to help and are often deliberately targeted for personal attacks. In the case of Covid-19, healthcare workers have had the highest risk of infection within the community, but as of August 2021, only 1.6% of those in poor countries had been vaccinated [37].The situation has not improved during the pandemic and attacks on healthcare facilities, transportation, and patients have become more frequent. More than half of the countries in need of assistance in the pandemic have experienced a long- lasting humanitarian crisis by 2020. The safety, health, and well-being of humanitarian workers must be further prioritised as part of the universal goal of health for all and protection of the most vulnerable.

Summary

Cooperative health interventions must focus on the alleviation of suffering and needs of patients, especially those living in poor and marginalized communities, and promote collaborative efforts to try to mitigate what the ill see as a threat to their existence by promoting appropriate use of available resources. Universal health coverage can be a starting point for improving the quality of health systems. Governments should start by establishing the highest quality in their services, specifying the level of competence and expertise that people can expect.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

1. Cassell, LT, Cassell, AK. Health Care Assessment of Health Care Delivery and Outcome - A West African Review. Saudi J Med. 2019. doi:10.36348/SJM. 2019. v04i11.001

2. International Finance Corporation. The Business of Health in Africa: Partnering with the Private Sector to improve People´s lives. Washington /District of Columbia). 2007

3. WHO. Public financing for health in Africa: From Abuja to the SDGS. World Health Organization, 2016

4. Merdad, L, Ali MM. Timing of maternal death: levels, trends, and ecological correlates using sibling data from 34 sub-Saharan African countries. PLoS ONE. 2018; 13 (1):20189416

5. Griego, M, Turner J. Maternal mortality: Africa´s, burden, toolkit on gender, Transport and maternal mortality. World Bank, 2005

6. UNICEF 2019https://data.unicef.org/topic/maternal-health/maternal-mortality/

7. WHO. Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2015.

8. Fundamental principles of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. Geneva: International Committee of the Red Cross. ICRC). 1986 (https://www.icrc.org/en/fundamental -principles, accessed 23 February 2018.

9. Integrating palliative care and symptom relief into the response to humanitarian emergencies and crisis. A WHO Guide 2018

10. Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, Jordan K, Leslie HH et al. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health. 21018; 6:2 1196-252.

11. Astudillo W, Mendinueta C, De la Fuente C, Salinas A. La cooperación internacional en Oncología y Cuidados Paliativos. En: Medicina Paliativa. Cuidados del enfermo en el final de la vida y atención a su familia. Editado por W. Astudillo, C. Mendinueta y E. Astudillo. Eunsa, 6 Edición, 2018; 1019- 1045

12. Boyle P, Ngoma T, Sullivan R, et al. Cancer in Africa: The way forward. Ecancer 2019, 13:953. www.cancer.org. doi: https://doi.org/103332/ecancer.2019.953

13. WHO Safe Childbith Checklist,2015. http://www.who.Int/patientsafety/implementation/heclists/checklists/childbirth/en/.

14. Adesina A, Chumba D, Nelson AM, et al. Improvement of pathology in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Oncol. 2013; 14: e152-57

15. Atun R, Davies Jl, Gale EAM et al. Diabetes in sub-Saharan Africa: from clinical care to health policy. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017; 5-622-67

16. Leslie HH, Spiegelman D, Zhou X, Kruk ME. Service readiness of health facilities in Bangladesh, Haiti, Kenya, Malawi, Namibia, Nepal, Rwanda, Senegal, Uganda and the United Republic of Tanzania. Bull World Health Organ. 2017; 95:738-48

17. Mukadi P, Lejon V, Barbé B, et al. Performance of microscopy for the diagnosis of malaria and human African Trypanosomiasis by diagnostic laboratories in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: Results of a nation-wide external quality assessment. PLoS One. 2016; 11: e146450

18. Alshamsan R, Lee JT, Rana S, et al. Comparative health system performance in six middle-income countries: cross-sectional analysis using World Health Organization study of global ageing and health. JR Soc Med. 2017;110:365-37

19. WHO UNICEF. Water, sanitation and hygiene in health care facilities: status in low- and middle- income countries and way forward. 2015: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/154588/1/9789241508476_eng.pdf.(accessed February 13,2018

20. Uwemedimo OT, Lewis TP, Essien EA, et al. Distribution and determinants of pneumonia diagnosis using Integrated Management of Childhood Illness guidelines: a nationally representative study in Malawi. BMJ. Glob Health. 2018; 3:2000506

21. Goss, PE, Lee BL, Badovinac-Crnjevic T, et al. Planning cancer control in Latin American and the Caribbean. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:391-436

22. Chapman CR, Gavrin J. Suffering: the contributions of persistent pain, Lancet. 1999; 26:2233-7

23. Knaul FM, Farmer PE, Krakauer EI, et al. Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief - an imperative of universal health coverage: the Lancet Commission report. Lancet. 2018;1391- 454

24. Sleeman KE, de Brito M, Etkind S, Nkhoma K, et al. The escalating global burden of serious health- related suffering: projections to 2060 by world regions, age groups and health conditions. Lancet Global Health; 2019; 7<879. DOI. 10.1016/S2214-109x(19)30172X

25. Astudillo W, de la Fuente, C, Mendinueta C, Astudilllo X, and Santamaría D. Más allá de la colina y de la selva: una aproximación sobre la terminalidad en Camerún y África. EIDON, n 45:118-132 DOI: 10:10.13184/EIDON.45.2015:118-131

26. UNAIDS. AIDSinfo. 2017. http://aidsinfo.unaids.org

27. The WHO Member State Mechanism on Substandard and Falsified Medical Products. https://www.google.com/search?q=who+global+surveillance+and+monitoring+system+for+substand ard+and+falsified+medical+products&rlz=1C1CHBD_esES9

28. https://www.efesalud.com/Africa-medicamentos-falsos

29. Gracia D. La práctica de la Medicina. En: Bioética para clínico Editado por A. Couceiro. Editorial Triacastela. Madrid. 1999; 95-108

30. Rivilla F, Epílogo E: Atlas de Patología Médico quirúrgica en África, editado por Bento BL, Gutiérrez MA, Martínez MI, Rivilla F, Villalonga A. Paliativos sin Fronteras, San Sebastián, 2021

31. Anyanwu SNC, Egwuonwu OA, Ihekwoaba EC. Acceptance and adherence to treatment among breast cancer patients in Eastern Nigeria. Breast. 2011;20(2)S51-3

32. Asuzu, CC, Akin-Odanye, EO, Asuzu MC, Holland J. A sociocultural study of traditional healers role in African health care. Infectious Agents Cancer. 2019;14:15 https://doi.org/10.- 1186/S13027-019-0232-y

33. Alma-Ata Declaración. https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2012/Alma-Ata-1978 Declaracion.pdf

34. Sama M, Nguyen V-K. Governing health systems in Africa. 2009 Codesria. www.africanbookscollective.com

35. Genital HPV infection - Fact Sheet. https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv.htm

36. Allsop MJ, Powell RA, Namisango E. The state of mHealth development and use by palliative care services in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of the literature. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care. 2016; 0:1-9. doi 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-001034

37. Langlois EV, Dey T, Shah MG. More than honour, humanitarian health-care workers need life- saving protection. Lancet. 2021. https//:doi.org/10.1016/S10140-6736(21)0189324

Received: October 04, 2021;

Accepted: October 24, 2021;

Published: October 29, 2021.

To cite this article : Astudillo W, Rivilla F, Comba J, et al. Foundations for Healthcare Workers in West and Central Africa. British Journal of Cancer Research. 2021; 4:3.

©2021 Astudillo W, et al.